Metasearch systems are based on just-in-time processing, whereas Google Scholar, like other federated searching systems, is based on just-in-case processing. This underlying technology, along with Google Scholar's exceptional capabilities, accords Google Scholar a unique position among other scholarly resources. However, a year after its beta release, Google Scholar is still facing a number of challenges that cause librarians to question its value for scholarly research. Nevertheless, it has become popular among researchers, and the library community is looking for ways to provide patrons with guidelines for the most beneficial manner of using this new resource.

Metasearch systems have several advantages over Google Scholar. We anticipate that in the foreseeable future, libraries will continue to provide access to their electronic collections via their branded, controlled metasearch system.

Keywords

Metasearch, federated search, CrossRef CrossSearch, relevance ranking, Google Scholar, search engine, clustering search engine

Introduction

Google as a Web search engine has undoubtedly had a great impact on all those who search for information on the Web. The instant response, huge repositories, sophisticated search mechanism and relevance-ranking feature have combined to make Google the most popular Web search engine.

In late 2004, Google launched several exciting products, one of which is a beta version of Google Scholar. Aiming to provide a single repository for scholarly information, Google Scholar enables users to search for peer-reviewed papers, theses, books, preprints, abstracts, and technical reports in many academic areas. Furthermore, according to information released by Google, Google Scholar arranges results by relevance, taking into account the number of times that the item has been cited in scholarly literature, as well as other criteria. Equipped with this unique ranking process, unparalleled hardware resources, sophisticated crawling techniques, and access to published materials, Google is positioning Google Scholar to be an essential resource for the scholarly environment. In the not too distant future,

Google is likely to be facing rivals such as MSN and Yahoo!, who may offer similar products.

Still at the beta stage a year after its initial launch, Google Scholar has stimulated lively debate in the library community. Of particular interest to many is the question of whether Google Scholar is a potential competitor of metasearch systems and, if so, whether it will replace them or coexist with them as yet another channel to scholarly information.

Metasearching and federated searching

Before evaluating Google Scholar and its impact on the scholarly environment, let us examine the historical roots of the methodologies underlying systems such as Google Scholar.

We will start by clarifying the terms 'metasearch system' and 'federated search system' as used in this paper. These terms are frequently interchanged, but for our purposes, we would like to draw a distinction.

Metasearching, also known as integrated searching, simultaneous searching,

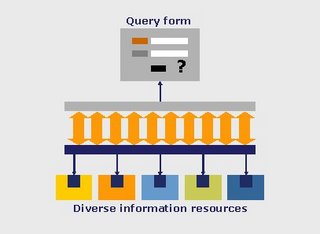

cross-database searching, parallel searching, and broadcast searching, is a process in which a user submits a query to numerous information resources simultaneously. The resources can be heterogeneous in many respects: their location, the format of the information that they offer, the technologies on which they draw, the types of materials that they contain, and more. The user's query is broadcast to each resource, and results are returned to the user.

The development of software products that offer metasearching relies on the fact that each information resource has its own search engine. The metasearch system transmits a user's query to that search engine and directs it to perform the actual search. Upon receiving the results of the search, the metasearch system displays them to the user. This process involves, first, the adaptation of the query's format to the specific requirements of the search engine at the target's end, and next, the conversion of the results to a unified format. The unified format later enables the metasearch system to process the results further - including displaying them in a consistent manner, merging them, and de-duplicating them.

We can describe metasearching as just-in-time processing. That is, instead of pre-processing the data, the metasearch system processes it only when the user launches a query.

Metasearch systems, therefore, hold information about how a resource can be searched and how results can be extracted from it, but they do not contain any of the data that is stored in any of the resources that they can access. For an in-depth discussion of metasearching.

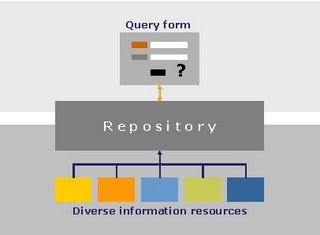

In federated searching, a wealth of information is incorporated into a single repository that can be searched. In this model, the information is processed prior to the user's search. From the end-user's point of view, federated searching and metasearching may seem similar, because both provide a single interface to multiple resources, but they actually differ in many respects. The pre-processing taking place in a federated searching environment, which we can describe as just-in-case processing, offers new opportunities regarding search methodologies and the presentation of results. For example, a ranking algorithm can be applied to each data element stored in the repository, unrelated to any future user query. Such an algorithm can take into account the number of times that an article has been cited, the number of articles that the author has published, the number of times that a book has been borrowed, a journal's impact factor, and other parameters. A federated searching system can use the calculated rank to better evaluate the relevance of the specific item once it has been retrieved as the result of a query

Looking back a few years, we can see that the need for a single search interface to multiple resources arose some time ago, and, in fact, metasearching and federated searching have been available for quite some time. Such systems originated in a variety of environments; for example, Elsevier, a publisher offering numerous journals, created a federated search mechanism enabling its users to search all its e-journals through its ScienceDirect service. As Elsevier acquired other publishers, it was able to add their journals to the same platform.

Database vendors developed similar mechanisms. For example, Ovid provides a single interface to a few hundred databases that it publishes, and still retains them as separate databases. Commercial organizations were not the only ones that addressed the need for a single search interface; several large research institutions created a local environment based on federation. For example, the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the OhioLink consortium in the United States, the University of Toronto in Canada, the Technical Knowledge Center of Denmark (DTV), and the Max Planck Society in Germany all offer large, diverse collections of e-journals that they store locally. These institutions have implemented federated searching to provide a single search interface across their electronic collections.

However, not all organizations have the resources to adopt this just-in-case approach. Furthermore, with the rapid increase in the number of heterogeneous resources that institutions offer their users, a single federated searching system can serve only as a partial solution.

Library system vendors took a major step toward metasearching when they implemented the Z39.50 search-and-retrieve protocol, which enables them to provide access to library catalogues. Despite the wide adoption of this protocol, this solution could not scale up to provide a single access point to numerous resources. Hence, we saw the emergence of dedicated metasearch systems as we know them today.

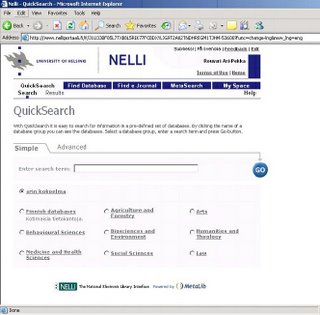

The market's quick acceptance of metasearch systems indicates that libraries do indeed have a need that these systems can fulfil. For example, well over 500 institutions have acquired the Ex Libris MetaLib system since 2001, and many other such metasearch systems are offered in the marketplace. The ability to provide a single, friendly interface to multiple resources enables libraries to better address the changing expectations of their users, users who in the meantime have become accustomed to Google and Amazon.

Libraries have not only adopted metasearch systems at a rapid pace, but they have also advocated the development of new standards related to the metasearch process and are sharing their concerns with information providers and metasearch system vendors about the accuracy of searches and the burden that remote searches place on target resources. The active involvement of information providers kicked off the NISO Metasearch Initiative, whose aim is to provide the industry with a set of standards that will facilitate and optimize metasearching. This NISO initiative has been the focus of much discussion in the last couple of years, and apparently numerous stakeholders - publishers, librarians, and metasearch system vendors - agree on the value of formulating standards in this area.

Of particular interest to the providers of metasearch systems are the Semantic Web developments spearheaded by Tim Berners-Lee and the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). A Semantic Web approach would facilitate the interaction between a metasearch system and any number of target resources without requiring prior programming for each target resource. The ideal solution is for the metasearch system to receive resource-specific information at the time of the actual interaction and formulate the flow of the interaction on the basis of this information.

No comments:

Post a Comment