Google Scholar is easy to use. It has a familiar look and feel, and it is accessible from anywhere, including Internet cafés all over the globe. It is extremely fast, it covers a broad, heterogeneous range of information sources, and it does not require any specific query structure. Now let us look at some other aspects of Google Scholar that might shed light on its usefulness as a scholarly resource.

The major questions about Google Scholar relate to the scope, coverage, and accuracy of the content. Google Scholar does not disclose information about its content. At the SFX-MetaLib User Group (SMUG) meeting that took place in June 2005 at the University of Maryland, Anurag Acharya, the chief engineer of Google Scholar, talked about providing the "best possible scholarly search" and a "single place to find scholarly materials" covering "all research areas, all sources, all time". At the time of the writing of this article, the goal has not been fully achieved.

First, scholarly materials provided by many publishers, for example, Elsevier, the American Chemical Society and Emerald, are not yet included in Google Scholar, although the metadata describing some of these publishers' materials finds its way to Google Scholar via other channels, such as the National Library of Medicine's PubMed.

Second, the material that Google Scholar incorporates from a publisher does not always provide complete coverage. Furthermore, updates are not frequent enough to always include the most recent articles.

An enlightening review by Peter Jacso compares the coverage of Google Scholar and that of the original publisher's repository; the results of his comparison indicate that Google Scholar provides only partial coverage. Although the review was published in December 2004, the situation is similar almost a year later. For example, a search in Wiley InterScience for "tsunami" in the title field yields seven results, whereas a search in Google Scholar with the scope limited to Wiley InterScience yields only five results - articles published in 2005 do not appear. A search in Google Scholar for "antimatter", with the scope limited to the Institute of Physics, misses three articles (published in 1973, 1999, and 2003).

When a user knows exactly what he or she is looking for, the partial coverage problem is less serious because the person is aware that the item is missing and can check other databases, such as those that are targeted to the user's area and are more up to date. However, when users are looking for content without knowing which articles, books, or other materials have been published in that area, they might miss valuable information by relying solely on Google Scholar. For some users, such as undergraduates who are looking for any available material, such partial coverage matters less; for researchers, the unrecognized absence of relevant material can be critical.

Another issue worth noting is the definition of scholarly materials. Here, too, we are not sure how Google evaluates what it finds and what criteria it uses for categorizing materials as scholarly or not, except for the obvious cases in which it harvests publishers' sites.

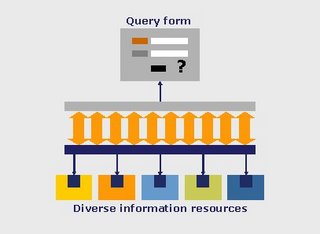

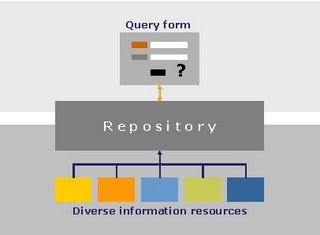

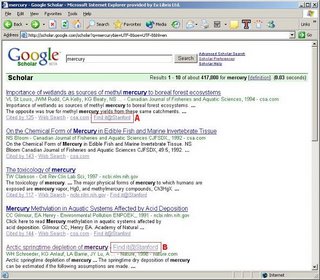

Google Scholar offers a multidisciplinary repository. Unlike metasearch systems that by nature provide both the library and the end-user with tools to define the scope of a search and send a query to only the most relevant resources, Google Scholar, by default, uses its entire repository to provide results. Hence, a search for "mercury", for example, yields results relating to the planet, the chemical element, and the musician Freddie Mercury (though the latter does not appear at the top of the list). This approach clearly facilitates interdisciplinary research but can hamper the effort to focus on a specific discipline.

The problem of the search scope has resonated enough to bring about the introduction of a new feature in the Google Scholar advanced search interface - the option to limit the search to one or more broad subject areas: biology, life sciences, and environmental science; business, administration, finance, and economics; chemistry and materials science; engineering, computer science, and mathematics; medicine, pharmacology, and veterinary science; physics, astronomy, and planetary science; social sciences, arts, and humanities. However, libraries cannot control this list, and the issue of whether the results of a search limited to a specific subject area are, indeed, applicable to that area has yet to be examined. A quick test shows that among the articles that come up in a search for "Mars" in the subject area of social sciences, arts, and humanities is "History of water on Mars: a biological perspective", published by researchers from the Space Science Division, NASA Ames Research Center. We can safely conclude that this article is not related to the selected subject area. It seems that Google Scholar has developed automated procedures to categorize the materials that it harvests, but such procedures still fall short of the database providers' classification methods, which are based on careful, human processes.

One of the major contributions to the success of Google in general is the relevance-ranking feature. Usually people find what they are looking for on the first page of results, thanks to the PageRank algorithm that Google uses to evaluate each Web page prior to user queries and without any relation to them. This algorithm is based on the number of links that point to the page from other Web pages, the number of links that point to those other Web pages, and so on. For Google Scholar, the algorithm had to be changed because of the different nature of the data. According to the information on the Google Scholar Web site, "the relevance ranking takes into account the full text of each article as well as the article's author, the publication in which the article appeared and how often it has been cited in scholarly literature".

Here, however, we run into a few problems. First, because Google has not publicized its content or the manner in which it determines whether material is 'scholarly literature', we have no way of knowing whether the number of citations is complete and accurate. Furthermore, as Google does not always identify duplicates (probably because of the heterogeneous nature of the metadata that it discovers while crawling the Web), the number of citations may not be realistic. For example, when we search in Google Scholar for the article "Library portals: toward the semantic Web", Google Scholar shows that the article has been cited six times; nevertheless, when we click the 'Cited by 6' link and look at the citations carefully, we can see that one publication appears twice, as both the first and sixth citations. Moreover, at least two other known citations are missing altogether. Yet Google Scholar uses citations to determine relevance ranking.

Whether systems that enable searches across scholarly materials should display the results of users' queries by relevance is not a simple question to answer. Relevance, in at least some cases, depends on context. Relevant to whom? For what purpose? Does the same relevance apply to an undergraduate who is looking for material for an introductory course in physics and a scientist who is searching for recent publications related to current research? The student might need a well known article that is not new, but the scientist is almost certainly not looking for that article. Furthermore, the usefulness of an item depends on the discipline of the researcher; for example, the articles that come up in a search for "plague" will differ in their relevance to a scholar of twentieth-century French literature and to an epidemiologist.

Roy Tennant offers a noteworthy example in his presentation "Is MetaSearch Dead?". He searched for "tsunami" in Google Scholar, Google, and the National Science Digital Library (NSDL). The first page of results in Google Scholar yielded no items with general information that an undergraduate would find useful. In Google, the first page included three results with useful scientific information, seven relief effort sites, and at least seven sponsored links (advertisements). But the first page of results at the NSDL listed 20 sites with useful scientific information. Perhaps these sites are hiding somewhere in the Google Scholar result list, but it is doubtful that any user will be able find them among the tens of thousands of results.

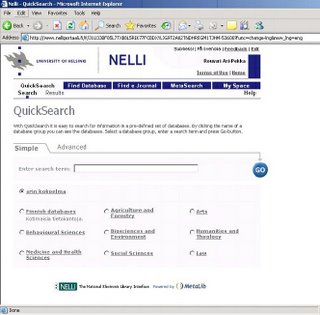

Interestingly, most bibliographic databases do not return results by relevance; such databases typically list results by date in descending order and enable the user to re-sort them by other criteria, such as author and title. Metasearch systems retrieve the results from the databases in the order set by each database and sometimes also provide options for other modes of display. For example, MetaLib from Ex Libris displays the results in the original order dictated by the database and also as one merged, de-duplicated list sorted by relevance. The end-user can re-sort the merged list by author, title, and date.

Google Scholar's choice of sorting criteria used for the display of scholarly materials represents a significant potential for power. People who are used to finding what they are looking for on the first page in Google are likely to adopt the same behaviour when using Google Scholar; thus highly cited items will gain more citations and will continue to appear at the top of the page. It is not obvious that this method of displaying results, the only one that Google Scholar provides, is indeed appropriate for scientific research.

One of the greatest advantages of Google Scholar, inherited from Google, is the simple interface, in terms of both design and functionality. Extremely intuitive, it is also available from any computer, with any browser. On the one hand, this interface is convenient for end-users, but, on the other, it does not allow for integration within a virtual library environment. Libraries typically want to provide their patrons with a complete user experience, encompassing content, design, and services, and they manage to do that quite successfully with their metasearch systems. With these systems, not only can libraries customize the user interface to create their own look and feel (typically for institutional branding), but they can also integrate their metasearch systems with their authentication environment, course management systems, and institutional portals; they have control over the resources that they offer, the categorization of those resources, the terminology, the display options, and the services that they provide for the end-users. Such services include a link to the library's holdings - be they electronic or print, local or remote; links to other relevant resources; functions that enable users to download records in the appropriate format, save and send citations, define alerts, create lists of favourite resources, and more.

Google Scholar, however, does not support integration in the virtual library environment. The Georgia State University library site, for example, makes an effort to introduce Google Scholar to its patrons, but when a patron clicks the link to Google Scholar, a new window opens without any university branding - the same Google Scholar page that users at any other library see.

Of much concern at the time that Google Scholar was launched was the lack of library control over the link to the electronic copy that Google Scholar provided for citations. Google Scholar did not address the 'appropriate copy' problem, despite the generally accepted solution offered by the OpenURL framework. As Herbert Van de Sompel, inventor of the OpenURL framework, explains, "This problem refers to the fact that such linking frameworks fail to provide links that lead from a citation of a journal article to the appropriate full-text copy of that article. A full-text link typically leads to a publisher-defined default copy of the article, which usually resides in the publisher's repository. However, access to the copy of the article that is appropriate in the context of a certain user may very well require the provision of an alternative link".

As a result of these concerns, Google Scholar was quick to adopt the OpenURL standard. Following a short pilot project with selected libraries, Google Scholar became officially OpenURL enabled in May 2005. If a library opts to take advantage of this compliance, Google Scholar provides library-defined links to the user's institutional link server, for example, SFX, for many of the displayed citations (as long as specific metadata elements, such as ISSN and DOI, are available). On the basis of the user's IP or the affiliation preferences that he or she has set, Google Scholar identifies the user as belonging to a specific institution. The provision of a link to the institutional link server puts the control back in the hands of the librarians and allows the users of Google Scholar to take advantage of library holdings and services.

Under the assumption that users are typically most interested in electronic full text, Google Scholar has been designed to display a link to the institutional link server in a prominent place - next to the title - when the electronic full text is available, and when it is not, the link is displayed with the other links, underneath the citation. For Google Scholar to be able to alter the display of the link according to the availability of the full text, libraries must provide Google Scholar with the details of their electronic holdings. SFX, the link server from Ex Libris, automates the provision of holdings information to Google Scholar so that this task does not become a burden on the library staff.

Many librarians, however, did not readily accept this requirement. First, it contradicts one of the fundamental concepts of the OpenURL framework: the library should have full control over the user experience regarding the delivery of services. Second, because Google is a commercial company, some librarians are concerned that providing Google Scholar with holdings information may serve Google for matters other than the provision of links and hence does not comply with their mission as educational or research institutions that are commercially neutral. And third, this move requires that libraries maintain the information in a form that Google Scholar can harvest. In his presentation at the SMUG meeting, Acharya offered compelling arguments for providing holdings data. He highlighted the benefits of having the links in Google Scholar and explained the Google Scholar philosophy of informing the user in advance of whether the desired service, in this case the link to the full text, is available. Assuring libraries that they have a partner they can talk to, he emphasized the need to "step out of the mutual comfort zones" and work together.

Finally we come to a question that continues to puzzle the library community: what is the business model that Google has adopted for Google Scholar? At the time of the writing of this article, the Google Scholar site was not displaying advertisements. However, Google Scholar was still in the beta phase. If this policy changes, libraries may reconsider providing their holdings to Google Scholar and promoting its use in their institution. As with many other questions concerning Google Scholar, we can only wait and see what happens.