Usenet groups, text-based discussion groups that cover literally hundreds of thousands of topics, have been around since long before the World Wide Web. Deja News used to be the repository of Usenet information until it sold off its archive to Google in early 2001. Google filled it out even further and relaunched it as Google Groups (http://groups.google.com). Its search interface, is rather different from the Google Web Search, as all messages are divided into groups, and the groups themselves are divided into topics called hierarchies.

The Google Groups archive begins in 1981 and covers up to the present day. Just shy of 850 million messages are archived. As you might imagine, that's a pretty big archive, covering literally decades of discussion. Stuck in an ancient computer game? Need help with that sewing machine you bought in 1982? You might be able to find the answers here.

Google Groups also allows you to form your own ad hoc groups to collaborate on or discuss topics. See the Google Groups tour (http://groups.google.com/intl/en/googlegroups/tour/index.html) for instructions on how to create your own newsgroup. You have to first choose where you want your group to be categorized, which means understanding the hierarchy.

Ten Seconds of Hierarchy Funk

There are regional and smaller hierarchies, but Usenet relies on alt, biz, comp, humanities, misc, news, rec, sci, soc, and talk. Most Usenet groups are created through a voting process and are put under the hierarchy that's most applicable to the topic. But you can create a group that's available via Google Groups without any input.

Browsing Groups

From the main Google Groups page, you can browse through the list of groups by picking a hierarchy from the front page. You'll see there are subtopics, sub-subtopics, sub-sub-subtopics, andwell, you get the picture. For example, in the comp (computers) hierarchy, you'll find the subtopic comp.sys, or computer systems. Beneath that lie 75 groups and subtopics, including comp.sys.mac, a branch of the hierarchy devoted to the Macintosh computer system. There are 24 Mac subtopics, one of which is comp.sys.mac.hardware, which has, in turn, 3 groups beneath it. Once you've drilled down to the most specific group applicable to your interests, Google Groups presents the postings themselves, sorted in reverse chronological order.

This strategy works fine when you want to read a slow (i.e., containing little traffic) or moderated group, but when you want to read a busy, free-for-all group, you may wish to use the Google Groups Search engine. The search on the main page works much like the regular Google search, except for the Google Groups tab and the associated group and posting date that accompanies each result.

The Advanced Groups Search (http://groups.google.com/advanced_group_search), however, looks much different. You can restrict your searches to a certain newsgroup or newsgroup topic. For example, you can restrict your search as broadly as the entire comp hierarchy (comp* would do it) or as narrowly as a single group such as comp.robotics.misc. You can restrict messages to subject and author, or restrict them by message ID.

Possibly the biggest difference between Google Groups and Google Web Search is the date searching. With Google Web Search, date searching is notoriously inexact (date refers to when a page was added to the index rather than when the page was created). Each Google Groups message is stamped with the day it was actually posted to the newsgroup. Thus, the date searches on Google Groups are accurate and indicative of when content was produced.

Google Groups Search Syntax

By default, Google Groups looks for your query keywords anywhere in the posting subject, body, group name, or author name.

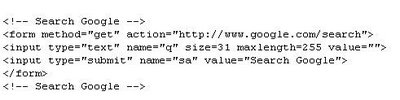

And, thanks to some special syntax, you can do some precise searching if you know the magic incantations:

insubject:

-

Searches posting subjects for query words:

insubject:rocketry

group:

-

Restricts your search to a certain group or set of groups (topic). The * (asterisk) wildcard modifies a group: syntax to include everything beneath the specified group or topic. rec.humor* or rec.humor.* (effectively the same) find results in the group rec.humor, as well as rec.humor.funny, rec.humor.jewish, and so forth:

group:rec.humor*

group:alt*

group:comp.lang.perl.misc author:

-

Specifies the author of a newsgroup post. This can be a full or partial name, or even an email address:

author:fred

author:"fred flintstone"

author:flintstone@bedrock.gov

Mixing Syntaxes in Google Groups

Google Groups is much more friendly to syntax mixing than Google Web Search. You can mix any two or more syntaxes in a Google Groups Search, as exemplified by the following typical searches:

intitle:literature group:humanities* author:john

intitle:hardware group:comp.sys.ibm* pda

Some common search scenarios

There are several ways you can mine Google Groups for research information. Remember, though, to view any information you get here with a certain amount of skepticism. Usenet is just hundreds of thousands of people tossing around links; in that respect, it's just like the Web.

Tech support

Ever used Windows and discovered there's a program running you've never heard of? Uncomfortable, isn't it? If you're wondering if HIDSERV is something nefarious, Google Groups can tell you. Just search Google Groups for HIDSERV. You'll find that plenty of people had the same question before you did, and it's been answered.

I find that Google Groups is sometimes more useful than manufacturers' web sites. For example, I was trying to install a set of flight devices (a joystick, throttle, and rudder pedals) for a friend. The web site for the manufacturer couldn't help me figure out why they weren't working. I described the problem as best I could in a Google Groups searchusing the name of the parts and the manufacturer's brand nameand, though it wasn't easy, I was able to find an answer.

Sometimes your problem isn't as serious but it's just as annoying. For example, you might be stuck in a computer game. If the game has been out for more than a few months, your answer is probably in Google Groups. If you want answers to an entire game, try the magic word walkthrough. So, if you're looking for a walkthrough for Quake II, try the search "quake ii" walkthrough. (You don't need to restrict your search to newsgroups; "walkthrough" is a word strongly associated with gamers.)

Finding commentary immediately after an event

With Google Groups, date searching is very precise (unlike date-searching Google's Web index), so it's an excellent way to get commentary during or immediately after events.

Barbra Streisand and James Brolin were married on July 1, 1998. Searching for "Barbra Streisand" "James Brolin" between June 30, 1998 and July 3, 1998 leads to over 48 results, including reprinted wire articles, links to news stories, and commentary from fans. Searching for "barbra streisand" "james brolin" without a date specification finds more than 1,800 results.

Usenet is also much older than the Web and is ideal for finding information about an event that occurred before the Web. Coca-Cola released New Coke in April 1985. You can find information about the release on the Web, of course, but finding contemporary commentary would be more difficult. After some playing around with the dates (just because it's been released doesn't mean it's in every store), I found plenty of commentary about New Coke in Google Groups by searching for the phrase "new coke" during the month of May 1985. Information included poll results, taste tests, and speculation on the new formula. Searching later in the summer yields information on Coke re-releasing old Coke under the name "Coca-Cola Classic."

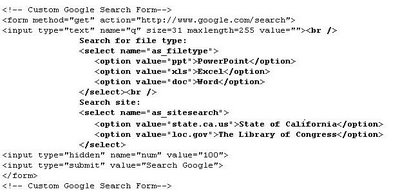

Advanced Groups Search

The Advanced Groups Search, is much like the Advanced Web Search and Advanced News Search.

Rather than fiddling with the special syntax detailed earlier, simply fill out the form, hit the Search button, and let Google Groups compose the query for you. You can restrict your search to a specific newsgroup or section of hierarchy (e.g., comp.os.*), a particular person, a particular language, or posts arriving in the past 24 hours, week, month, 3 months, 6 months, or year. You can even search for a particular message if you know the message ID. And since Usenet can be just as woolly as the Web, you might want to turn on SafeSearch.